Table of Contents

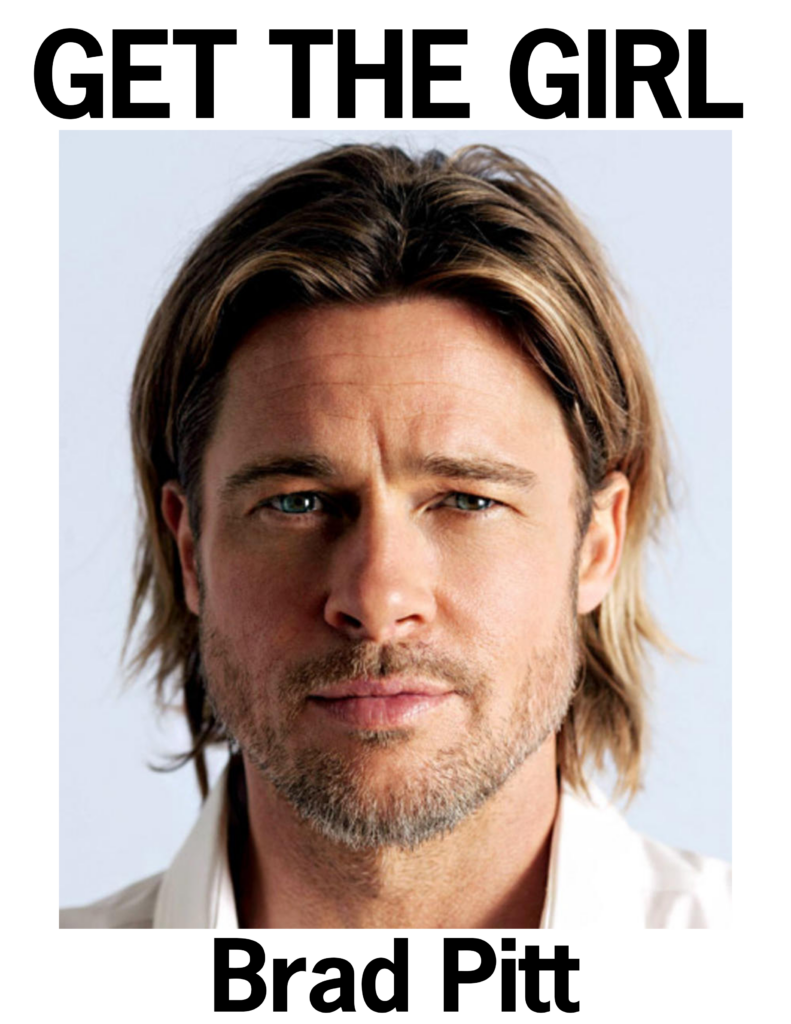

We would all read Brad Pitt’s dating book

“Don’t complicate things” say rich white men whose assistants are probably writing the books

We would all read Brad Pitt’s dating book

Imagine, if you will, a book by Brad Pitt revealing his iron-clad technique for getting dates:

- Go to a place where women are

- Smile

Think of all of the stories he’d have of getting dates with women by using this technique, each one bolstering the validity of his argument. For scientific heft, he could include research on the importance of proximity, and insights like different kinds of women are found in various places, like a church, calligraphy class, yoga class, or UFC match. But all of them have lots of women — you can even drop into a random Zoom meeting! Step #2 might turn out to be a little more nuanced: sometimes, a mere pout or look of longing will do.

That’s it! Just two steps. Anything else is just complicating the situation and is a waste of precious mental energy. Imagine the blog posts, the back cover:

Don’t make things harder on yourself. You don’t need style or fashion advice — just wear whatever you’d put on for a table read; no need to dress for a gala. Just brush your teeth and get your ass to a goddamn bar.

No discussions of hitting the gym; personal grooming; tips on confidence, body language, or feeling comfortable in your own skin. He wouldn’t have to think of how to best introduce himself or explain his job. No tips on dealing with rejection or the heartbreak of constant failure. No ideas for using one’s failures as a vehicle for self-discovery.

The book would sell millions of copies. After all, who wouldn’t believe what Brad Pitt had to say about women?

More importantly: who doesn’t want to believe that the answers to life are this simple?

We may not realize it, but most advice in the self-improvement/self-help/productivity realm is just as useful. Here’s another example:

Got that? Making progress in life is an easy, two-step process:

- Observe the gap between where you are and where you want to go

- Bridge the gap

In a few months, Simon & Schuster will publish Making Numbers Count: The Art and Science of Communicating Numbers, which I wrote with Chip Heath. (Heath is the New York Times bestselling author of Switch and Made to Stick; I am an elder millennial with student loan debt.)

I learned everything working with Chip, and as a result of said experience, I’ve been recovering from burnout/workaholism, re-examining my relationship with work, and researching new book ideas for the past year.

I’ve also been making constant little efforts to finally get my shit together on the marketing front. (If I’m writing self-help, I ought to be able to help myself, right?) In that spirit, I’ve been doing lots of personal work to get over the publishing block that’s kept me from blogging, writing newsletters, etc. for the past 10+ years. Since you’re reading this, I’m happy to report that I’ve made progress.

I’m also taking this opportunity to be very transparent about the fact that my progress has not come from the kinds of self-help, self-improvement, or productivity lessons out there. Why? The Brad Pitts of the world write most of the books on dating. Once you see this phenomenon, you can’t unsee it.

“Don’t complicate things” say rich white men whose assistants are probably writing the books

It’s easy to take advice from wealthy, well-known people who seem to have their shit together. Or even just people who seem to have their shit together, and are happy to report how easy the whole process was, in hindsight. To understand why that’s a bad idea, we can turn to the wisdom of what Amy Poehler said when she was looking for advice on writing a book:

“I asked people who have already finished books for advice, which is akin to asking a mother with a four-year-old what childbirth is like. All the edges have been rounded and they have forgotten the pain.” — Amy Poehler, Yes Please

She got tips like Stick to your guns! You can do it! but needed to hear if you find yourself crying alone in a closet, that’s okay. It’s part of the process.

Finishing and being on the other side of the finish line is, in itself, a sort of privilege. You’re on the other side of the pain.

The other annoying truth is that some people don’t have to travel as far to reach the starting line. Brad Pitt’s dating book would be useless for most of us: attractive people often don’t realize that they’re constantly being graded on a curve; they don’t have access to an alternate universe where they learn about the constant injustices of having a crooked nose or unfortunate jawline. They just know that getting women is easy — so surely, the world needs to hear about their two-step process.

So when we listen to successful people about how to become successful, we run into the real problem. The things that privileged self-help authors need to overcome their troubles don’t cut it for most of us. Money, power, and prestige allow people to be oblivious to the inner lives of others.

The term to know here is hypocognition — when we don’t know what we don’t know. An article by Kaidi Wu and David Dunning, “Unknown Unknowns: The Problem of Hypocognition,” states the issue well in the subhead: “We wander about the unknown terrains of life as novices more often than experts, complacent of what we know and oblivious to what we miss.”

People in socially dominant groups remain oblivious to their privilege because they are unaware of their benefits. Everyone is blind to how the path has been easy for them; we only see what’s been difficult for us. Privilege doesn’t mean an absence of hardship — just that you’ve been shielded from additional, structural hardships.

To really get how the path has been easy for him, Brad Pitt would have to constantly see his less-attractive friends strike out at bars — and understand, on a deep level, the energy required to remain positive while the world seems hell-bent on chipping away at your soul.

He’d need to practice empathy in order to develop it. The result would be a richer, more universal book — understanding that his experience is not a suitable stand-in for everyone’s experience. Without this reality check about what other people have to deal with on a daily basis, the advice often falls flat for people who aren’t like them.

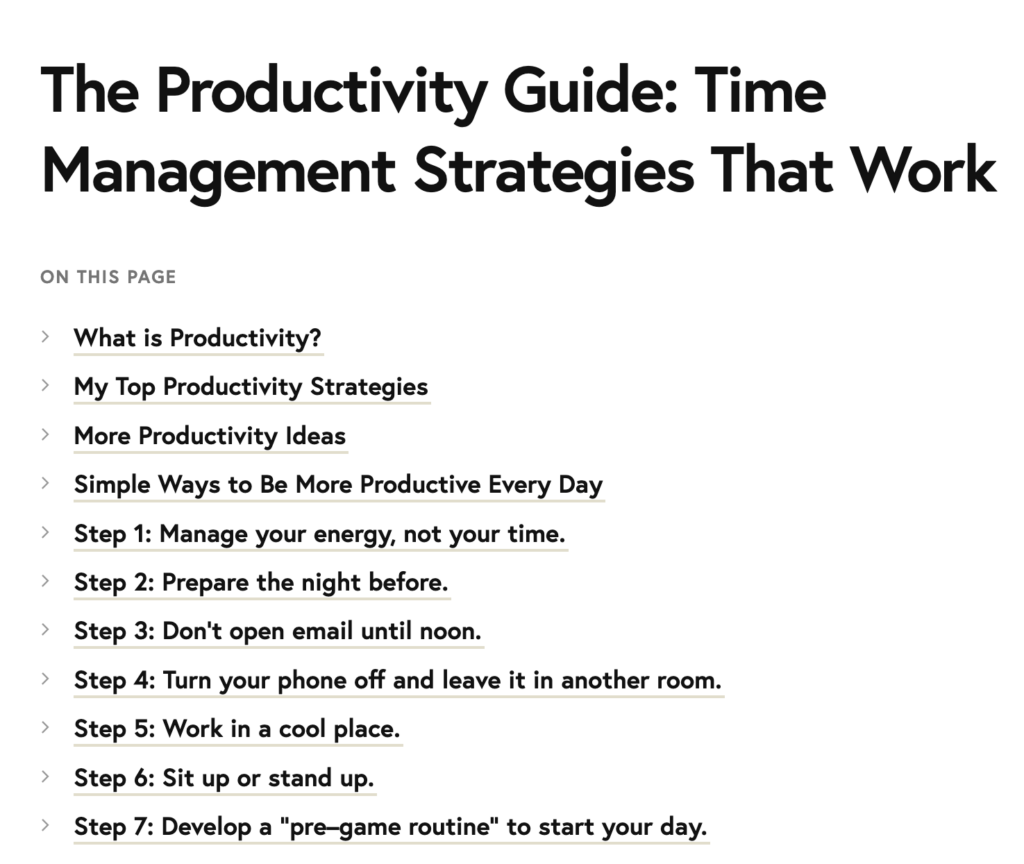

Here’s Atomic Habits author James Clear’s page on productivity:

Let’s appreciate the stunning “what works for me must apply to everyone else” of Clear’s list, whose “simple ways” to increase productivity apply to a very specific group:

- Knowledge workers with enough autonomy to have an entirely self-directed schedule.

- People whose bosses, coworkers, etc. are totally cool with them ignoring email for half of the day and adjusting all the thermostats.

- Those with so few responsibilities as to have spare time at night for “real thinking” and free time in the morning for a locker room dance.

- People who are not caregivers with potentially pressing tasks, and can completely disconnect for hours.

- People who seemingly do not have to think of anyone but themselves.

- Neurotypicals. “Sit up straight or stand up and you’ll find that you can breathe easier and more fully. As a result, your brain will get more oxygen and you’ll be able to concentrate better.” As someone with ADHD, I wish I would have known that my brain was merely suffering from a lack of oxygen!

It’s a narrowly-defined demographic, and one treated as the default rather than a privileged, specific class. These are not “ways to use your limited time on earth more effectively,” but “what James Clear does before he writes a blog post.”

Why the simplicity of privilege makes us feel like crap

True: Clear doesn’t mention everything that he had to go through before he was able to sit down, when the butterflies started and he got distracted at the keyboard. It took me a long-ass time to even get to the keyboard. My path to “productivity” online has taken 10 years, and a few more steps:

- Getting divorced from someone who expected me to be the default housekeeper

- Navigating the health care system

- Getting the right medication

- Managing mental health issues

- The belief that the only feedback won’t be from people criticizing me for not having a graduate degree in psychology, or otherwise belittling me

- Lots of therapy

- Lots of family therapy to disconnect from old codependent patterns that had me believing that my constant availability was required

- Talking to my father for the first time in 18 years and realizing how much baggage I was carrying around because of his mental health issues and inability to be present

- Getting sober

- Getting validation from an author I admire

- Realizing that the end result of this validation — feeling good about myself and my work— can’t rely on external factors

- Knowing, deeply and unconditionally, that what I write has value

- Not getting my self-worth wrapped up in the outcome, which I can’t control

- Loving myself and being okay with what I write

- Finally, when I was ready to sit down in my office next to my snoring dog in peace, realize that I’d run out of excuses…

See that? That is where James Clear’s list begins: prepping the night before; leaving his phone outside… by the time I got there, I was at least 15 steps and 10 years into the process.

Life has, historically, been easier for some people. Many of them seem to think that an accountability buddy is that “one, neat trick!” because that’s all they need. Good for them! Maybe they want to project an air of effortlessness. Or maybe it has been effortless. Or maybe they’re just whittling their message down to the simplest, most marketable answers.

But here’s what happens: the simple answers that wind up getting repeated and sold come with the unintended consequence of making us feel worse. We feel like there’s something wrong when we can’t just sit down and type; when we can’t just smile and get a date; when we’re not allowed to ignore email for a long time to get our “deep work” groove on. We read that the key to forming a habit is to “make it easy, fun, simple,” and feel ashamed when we can’t stick to a diet. We read about “manifesting” our soulmate — wanting to believe that all we have to do is believe — only to wind up spending a lot of time with our pets.

I spent a lot of time trying every single productivity app, every technique, and all the accountability systems. I blamed external factors — getting followers is harder as a woman! — without realizing was that I was letting that belief interfere with the belief that my work has intrinsic value, regardless of who sees it. I felt like there was something wrong with me for not being able to focus; I was having a hard time focusing because of the shitty messages I was getting from my ex, from toxic family members who wrote long emails detailing what they saw as mistakes in my book. (You know, the kind of message that’s really helpful to hear a week before your book comes out.)

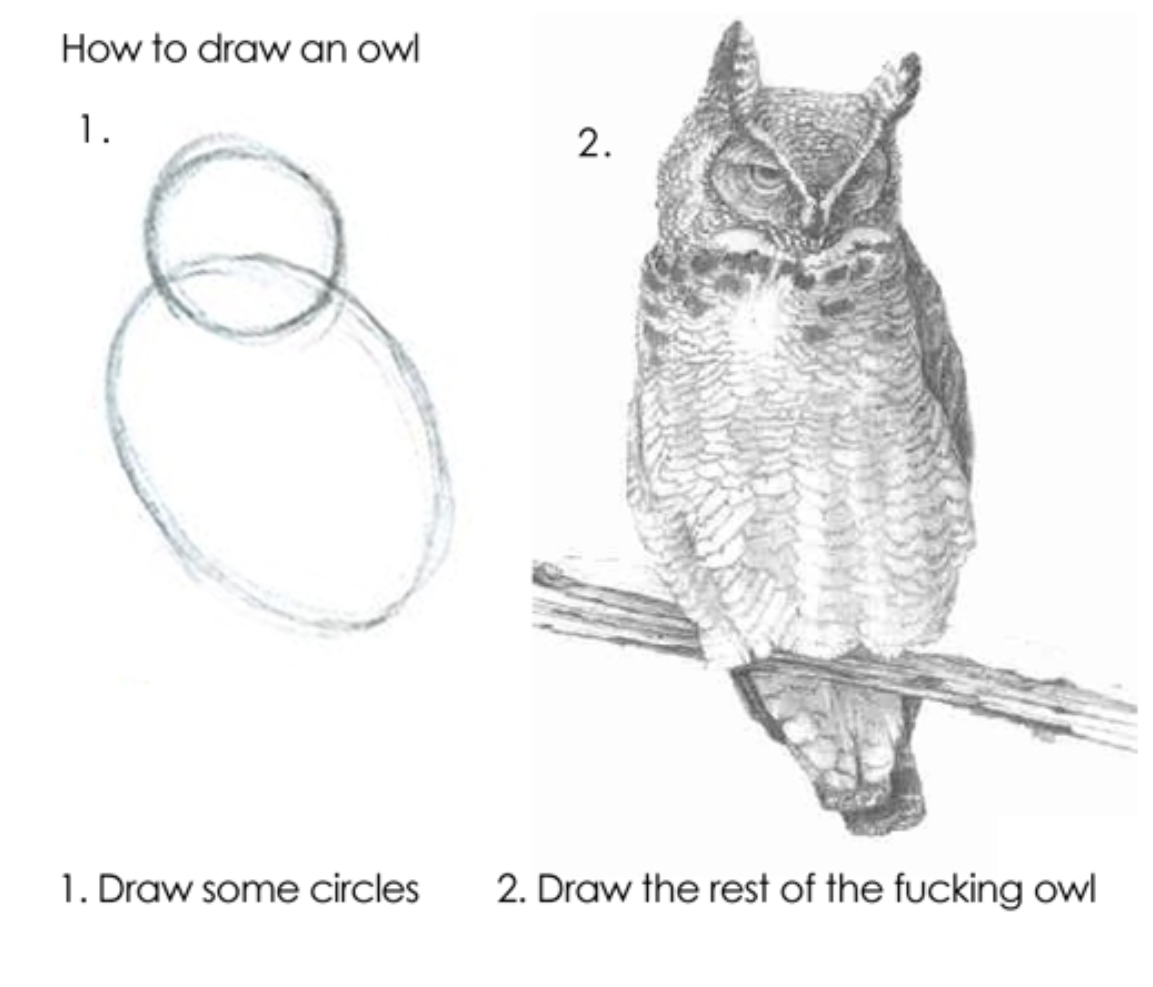

We feel like something’s wrong with us when we can’t just draw the rest of the fucking owl. We don’t realize that other people bought the damn owl drawings, were raised in an owl-drawing environment, or are hiding their own owl-drawing efforts.

We don’t realize how many people feel just as tired and frustrated as we do that elegant solutions aren’t enough.

Don’t feel ashamed if simple answers don’t cut it. Feel human.