Note: this is in no way a finished or completed essay—it's the beginning of a series. I teach workshops on Executive Communications and Sticky Frameworks if you want to sculpt your IP like a Heath.

I spent nearly four years as an apprentice to Chip Heath. Here's what I learned:

Time is finite, but everyone has to: eat dinner; have files somewhat organized; pay bills. Nothing is free, and everything in life has a tradeoff. If you have a family, a house, a class—those things need maintaining.

.png)

Thought leadership and academic research is what I call "HOA-approved creativity." You don't go there for genuinely groundbreaking academic ideas—you go there for ideas that have already been approved by various subcommittees and panels. It's a place for ideas that fit into an existing institution without breaking it. Increasingly, people consider academia a Ponzi scheme; research a house of cards. Chip was great at making complex ideas clear and developing corporate-friendly frameworks. He developed relationships.

All of this requires work to keep in balance.

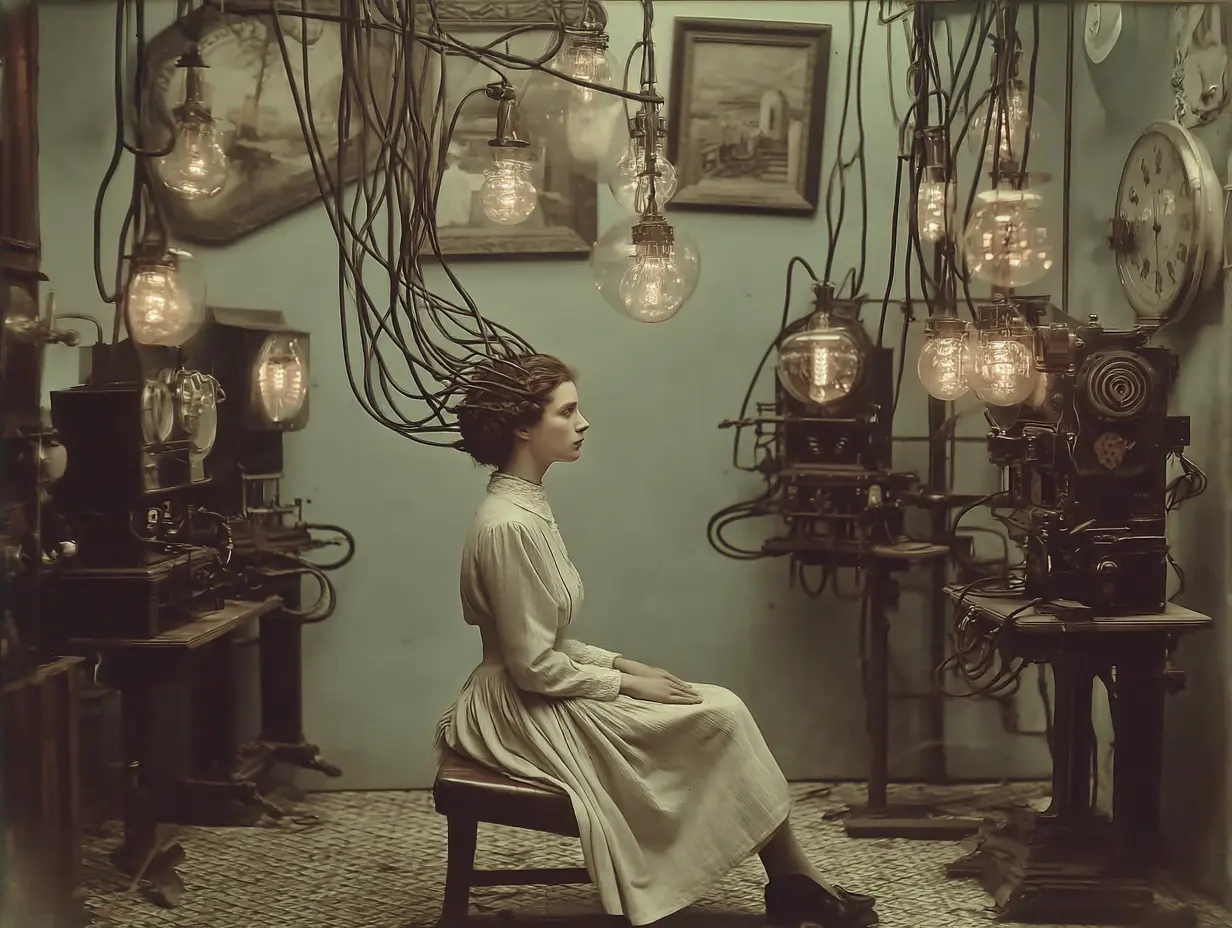

But none of this work would even be possible without complex scaffolding: organization, meetings, transcriptions, research. Food, mortgage payments, doctor's appointments.

And every minute someone spends doing one thing is a minute that they, by definition, can't spend doing another.

He thought that his burden was exhausting—but he devalued the real burdens that he imposed on others. It's easy for all of us to do this, without realizing it, if we've never been in someone else's position. We only see the 30 minutes spent cooking, not the hours at the grocery store, cleaning, budgeting. We only see the time spent teaching, not the hours of lesson planning, meeting with parents, and state exams. We only notice the people who work in IT when our computers crash.

Why does this matter at your workplace?

Every team faces coordination failures because so many burdens we place on others remain invisible—we don't realize how much time went into that document, that outline—the ownership, the mental load. It's too easy for people to underestimate how vastly different our lives are from others. When I was fixing up my house—living with tenants while essentially living in a construction site—I realized how often I thought, as a renter, that fixes were easy. Property and buildings are made of multiple systems (electrical, plumbing, windows, flooring, interior design); each fix needs to be assessed, budgeted, scheduled, maintained.

How difficult can it be, really? is usually said by people who have never had to do that thing.

The pattern I see everywhere:

- People aren't completely transparent about their workload; we don't see how our work fits into the big picture. We underestimate the contributions of others. We fail to see that senior execs can't do it alone; junior workers, once embedded, are not nearly as replaceable as others think. When they leave, nothing gets transferred because nobody else knows the full picture. There's no incentive to maintain legacy institutional knowledge.

- People burn out when the rewards are not distributed

What we could do differently:

Make the mental model visible. Write it down. Share it. Let others carry parts of it. The softest skill—and the most important for retention and culture—is learning to distribute the cognitive load. If you want your team to stay, stop hiding the mental model in one person's head. Make it visible. Share it. Let others carry it too.